After years of surpluses, California is heading into a deficit

SACRAMENTO, Calif. (AP) — Budget-wise, the first four years of California government.

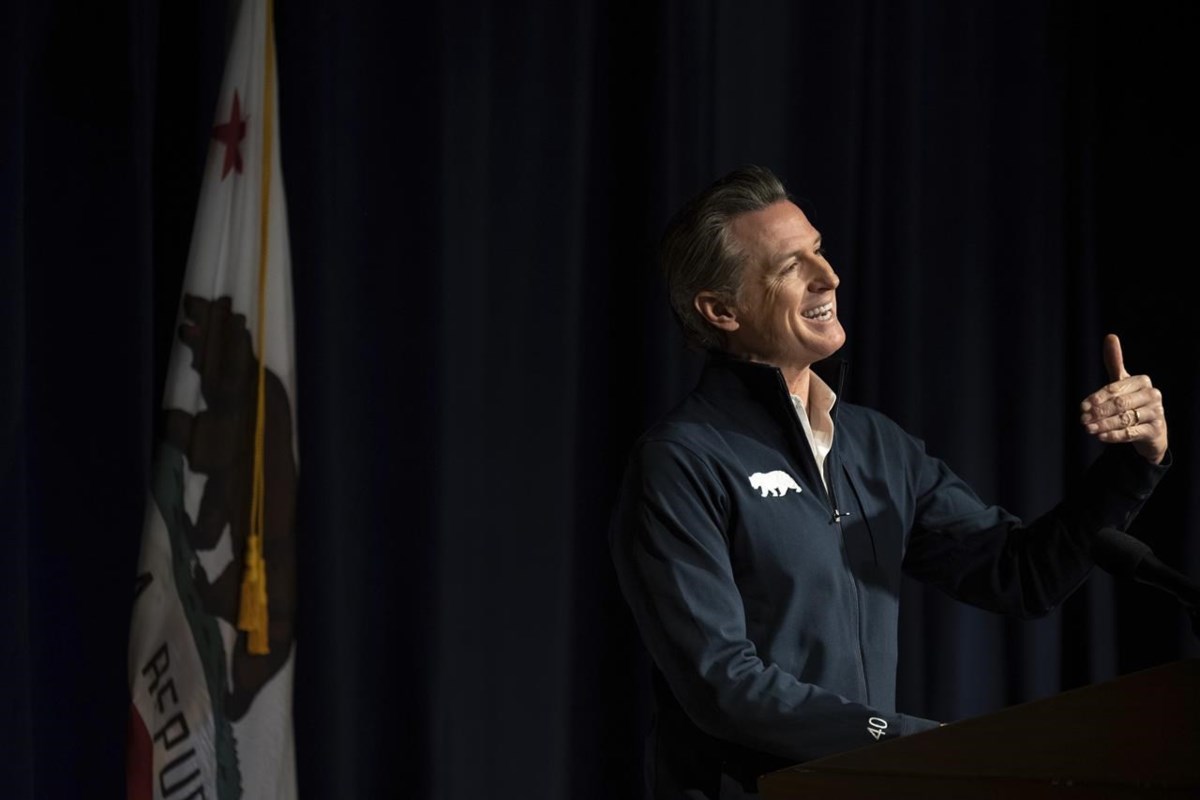

SACRAMENTO, Calif. (AP) — From a fiscal perspective, California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s first four years in office have been a fairy tale: a seemingly endless flow of money that has paid off to enact some of the most nation’s progressives while acting as a bulwark against a wave of conservative rulings on abortion and guns from the U.S. Supreme Court.

But just days into his second term, that dream seemed to come to an end. On Tuesday, Newsom announced that California would likely not collect enough taxes to pay all of its obligations, leaving a $22.5 billion hole in its budget.

The deficit was no surprise. Newsom and state budget writers have been reporting for more than a year that California is navigating economic headwinds. Tuesday’s news was that Newsom was offering his first plan on what to do about it.

Notably, Newsom chose not to dip into the state’s $35.6 billion savings account. And he offered no significant cuts to major programs and services, including promising to protect programs that pay for all children ages 4 to go to kindergarten and cover the health expenditure for low-income immigrants living in the country without legal permission.

Instead, Newsom plans to delay some spending while shifting some spending to other funding sources outside of the state’s general fund. He proposed $9.6 billion in cuts, including canceling a scheduled $750 million payment on a federal loan the state took out to cover unemployment benefits for people who lost their jobs. during the pandemic.

The validity of this plan will depend on the state of state finances after April 15, when most residents will file their taxes. Newsom and legislative leaders do not have to approve a spending plan until late June.

“We have a wait-and-see approach in this budget in terms of prudence and preparation,” Newsom said.

But Newsom appeared somewhat pessimistic about the future as he scaled back some of his ambitious climate proposals, slashing his much-heralded investment of $54 billion over five years to $48 billion.

Newsom tried to play down that cut, arguing that the $48 billion is still one of the biggest climate investments in the world and that the state would seek to recoup some of that lost money from other sources.

Still, it was enough of a cut to anger some climate groups who had been emboldened by the state’s commitment to tackling climate change in recent budgets.

“We must maintain our commitment to climate action every year. This proposed budget does not do that,” said Mary Creasman, CEO of California Environmental Voters. “Delaying these investments further will make the climate crisis even worse, and the cost of inaction will be much worse.”

Democrats control all of California’s state government, leaving Republicans little influence over policy and budget decisions. State Sen. Roger Niello, the top Republican on the state Senate budget drafting committee, said lawmakers need to focus on areas where the state is already spending a lot of money with little results, like homelessness.

“Generally speaking, we’re not necessarily suggesting we spend more, but spend smarter,” Niello said.

Despite the looming deficit, Newsom wants to give local governments an extra $1 billion for homelessness programs — the money he promised would come with an added dose of accountability after not be happy with the way some residents have spent state resources.

Public schools were mostly immune to the cuts in Newsom’s proposal, with one exception. Newsom cut $1.2 billion from a grant program that was intended to pay for arts and music education, but which most districts had planned to use to help pay off pension obligations, according to Kevin Gordon, a lobbyist who represents most public school districts.

Still, Gordon said it was “astonishing” that schools avoided deep cuts in a budget with a projected deficit of $22.5 billion.

Other deficit actions were more subtle. California is one of five states and the District of Columbia that tax people who refuse to purchase health insurance. Money from this tax goes into an account that is supposed to help low-income people pay their health insurance premiums. Newsom offered to take the money from that account — $333.4 million — and sweep it into the state’s general fund to help balance the budget.

“It’s exactly during an economic downturn that this kind of help getting coverage is even more urgent,” said Anthony Wright, president of consumer advocacy group Health Access. “We will advocate with the Legislative Assembly to see if this can be pursued.”

As the deficit drew attention on Tuesday, Newsom proposed new spending. He wants to spend $93 million to fight fentanyl, a synthetic drug similar to opioids that has caused countless overdose deaths. The money would come from the state’s share of the legal settlement with drug companies over opioids.

Newsom also wants to spend $3.5 million in education funds to provide all middle and high schools with at least two doses of naloxone — a drug used to reverse an opioid overdose.

“It’s a top priority if you’re a parent,” Newsom said. “I don’t think there’s a parent who doesn’t understand the significance of this fentanyl crisis.”

California’s deficit is a sharp turnaround from the previous year, when California had a surplus of about $100 billion. This money that came mostly from a booming stock market that made many Californians very wealthy, who then paid taxes on this new found wealth.

Since then, attempts by the federal government to control inflation have had a chilling effect on the economy, meaning the wealthy are don’t make that much money. That’s significant in California, where the top 1% accounts for nearly half of all state income taxes.

So far this year, California’s tax revenue has been well below expectations. If these declines continue, additional measures may be needed to cover the deficit.

“Business trends in the stock market and the technology sector are further depressing state revenues,” Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon said. “This June, the large reserves built over the past decade can be important in protecting progressive California investments.”

___

Associated Press reporter Sophie Austin contributed to this report.

Adam Beam, The Associated Press

Comments are closed.