The Female Gaze: Female Artists on the Male and Female Form | art for sale

How old is the male gaze? The term, which was coined by British art critic John Berger in 1972 – and popularized by film critic Laura Mulvey soon after – marks half a century this year. However, the male objectification of female forms in art is, we can safely say, somewhat older. The feminine gaze, as a concept and a force within visual culture, is more recent and, perhaps, therefore, much more vital. In these works, female artists give agency to female figures and offer a different view of male subjects. If the artwork on your wall shows a bit of sexism, we highly recommend you consider adding a few of these beautiful treasured pieces.

Mickalene Thomas – Jet Blue #11 (2021)

In 2012, Mickalene Thomas’ mother died and the artist inherited her mother’s box of Jet magazines. The 20th century African-American lifestyle publication included, in addition to serious reporting, political coverage and fashion and beauty advice, glamorous semi-nude photography. For his recent series, Jet Blue, Thomas has appropriated these and other images to produce a body of work that offers the artist’s own meditation on the black female body. The models for Jet’s shoots were anonymous and, as Thomas said earlier this year, “I like to think I’m giving them power over what’s revealed – it’s looking them in the eye and talking to them. , having conversations with the image. Who are you? What do you do? Where are you from?

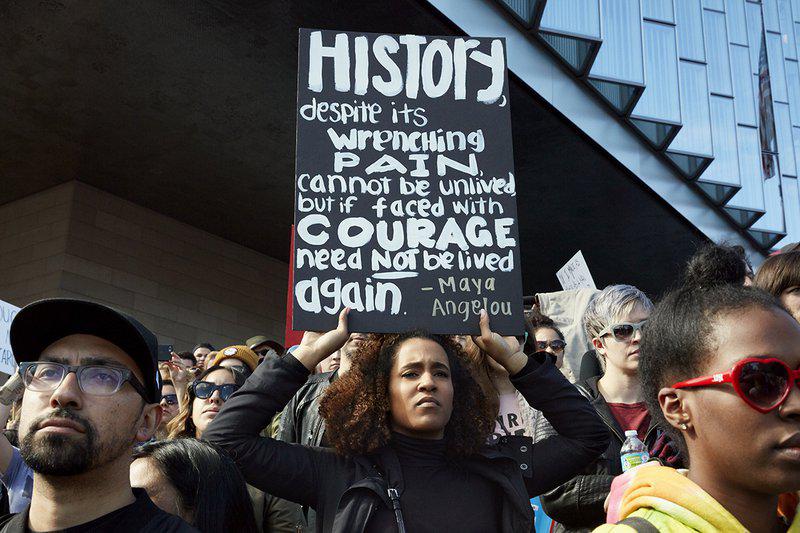

Catherine Opie- Herstory, Women’s March2017

American photographer Catherine Opie photographed and helped organize public protests. Indeed, she took on both roles at the first Women’s March, in January 2017. This rally, as you may recall, took place the day after President Trump’s inauguration and was organized to counter much of the perceived misogyny in the political narrative.

Opie ended up donning a safety vest to help herd the crowd, but eventually had to take it off. “After a while, I said to myself no! I can not do that; I have to do my job! she told Artspace. This photo was taken on the steps of the federal courthouse at 350 W 1st St, Los Angeles, as marchers began to settle into a still crowd and listen to speeches.

“The steps and the way the light was reflecting off the building across the street, you turn around and you’re like, ‘OK, there’s this amazing person holding this sign,'” recalls the artist. “I was reacting to what she was holding. It was just a beautiful moment. And it wasn’t just in the United States, it was all over the world.”

Kim Gordon– Air bnb silver lake2018

In 2011, musician and artist Kim Gordon split from romantic partner and Sonic Youth co-founder Thurston Moore. After their separation, Gordon left the East Coast to return to his hometown of Los Angeles, initially staying in properties rented through Airbnb. The simple, minimalist interior aesthetic found in many Airbnb homes inspired her 2019 solo exhibition, She Bites Her Tender Spirit, at Dublin‘s Irish Museum of Modern Art.

“A room is marked in a certain way, all the art, everything fits,” she said of the Airbnb aesthetic, “the toiletries in the bathroom are maybe of the same color as the paints.” The title of this show was taken from a poem by Sappho, and Gordon also channeled the poet’s point of view into these works, which reflect feminine beauty while simultaneously trying to evoke a more visceral and urgent vision of feminism. contemporary.

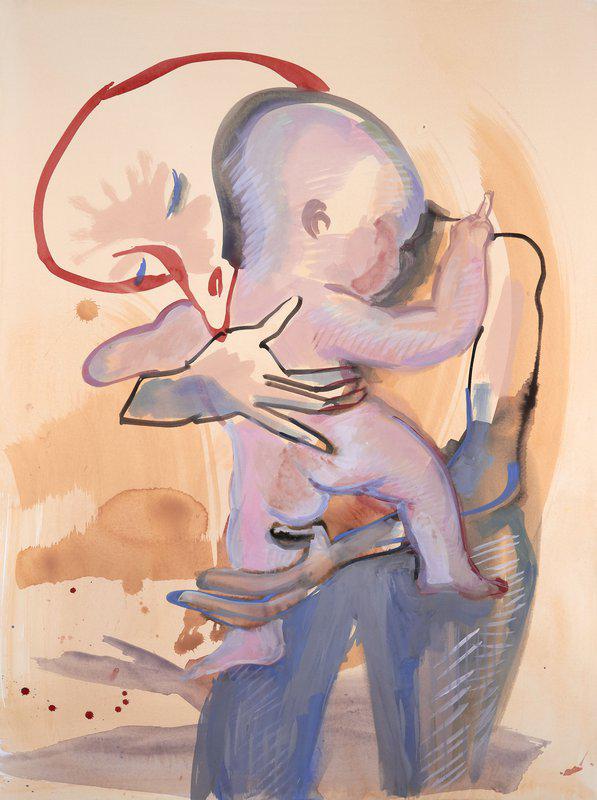

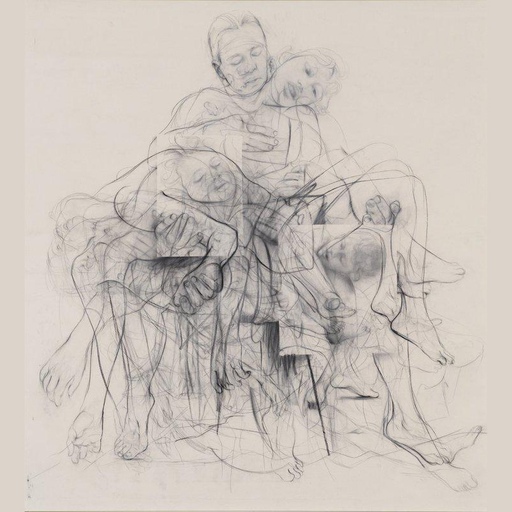

Camille Henrot Native language2020/2021

The feminine trope of the perfect mother is almost as rigid as that of the great feminine beauty. Henrot, an award-winning French artist, plays with this parental paradigm in her work, Mother Tongue. “You would think it’s a traditional depiction of a mother kissing her child, but it also looks like Cronos, devouring the child a bit,” she told Artspace. “The arm that carries the child is weak and exhausted, in contrast to the opulence and plumpness of the child’s body.

Henrot herself had become a parent before the work was created, but she dislikes an autobiographical reading, instead inviting viewers to consider the broader attributions of parenthood. “To me, parenting is a very interesting area or source of material because of how messy it is.” she says. “It’s complex, ambivalent and unstable. There is tenderness but there is also anger. There is attraction but there is also repulsion. And if you pull those strings, everything comes together: sexuality, love, death and much more.

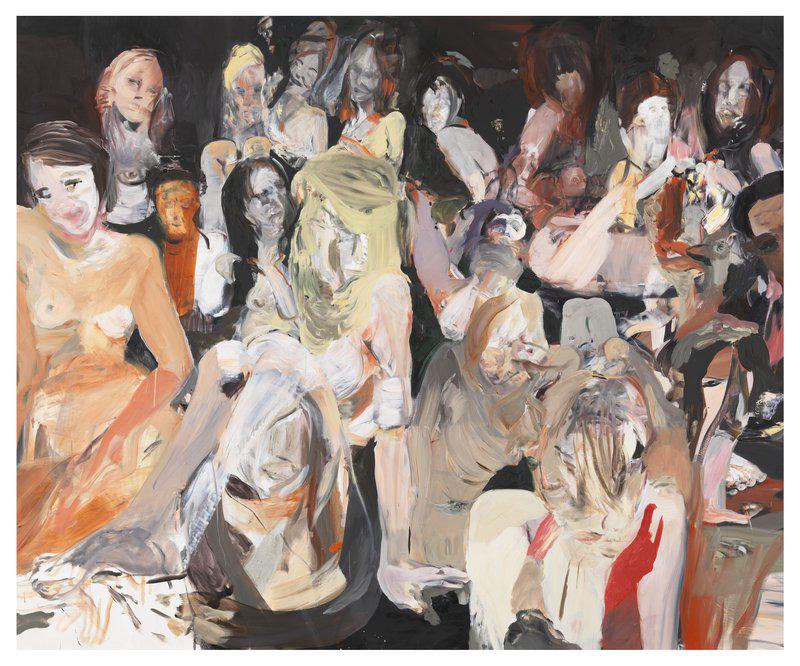

Cecile Brown – All the nightmares came today2012/2019

Rock scholars may recognize the source material from Brown’s image and its title. This work is one of many inspired by the group nude photography that graced the inside and outside sleeves of Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland (packaging varied from country to country and from year to year).

The title, meanwhile, is a line from David Bowie’s 1971 song, Oh! You pretty things. The photo, which featured women from the London club scene, none of whom were professional models, might have been considered exploitative at the time, but Brown reclaims the image. “Women dominate, their spectral forms slip in and out of visibility, their faces alternate between fusion and mask,” writes Jason Rosenfeld in Brown’s Phaidon monograph. “Women’s eyes follow you everywhere, and the source material, as in much of Brown’s art, fades as she claims the subject matter for herself.”

Nan Goldin– Valerie in the taxi, Paris, 2001, 2004

In the fall of 1995, Nan Goldin was in Paris to shoot a feature film for the New York Times, portraying American model James King. There, in the offices of French designer Jean Colonna, Goldin met former model-turned-designer and publisher Valérie Massadian. The couple became close friends; Massadian worked for Goldin; Goldin has photographed Massadian — nude, in bed, as well as in more public places, like this shot of her in the back of a taxi.

This image from 2001 captures something of their friendship and something of the moment. Admire Valerie’s anxious face, as she and Goldin weave their way through the lit streets of Paris, and you might also think of a time when failure or success was just a taxi ride away.

Jenny Saville – Chapter (for Linda Nochlin)2016/2018

Linda Nochiln is, of course, the American art historian who wrote the 1971 article, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, in which she described the institutional barriers that prevented women from succeeding in arts.

Saville – a real success, and an artist with a very long view of art history – seems to answer Nochlin’s question with her own sensual, moving work, suggesting bodies at work and at rest on a large period of time.

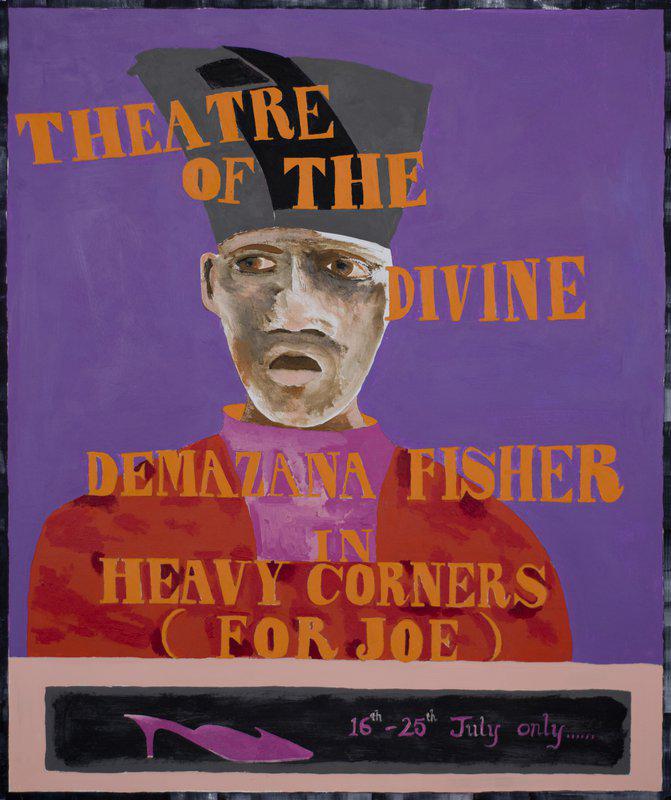

Lubina Himid – Theater of the Divine2019

Himid’s work imagines a fictional actor called Demanzana Fisher, starring in an imaginary play. It’s a typically fantastical, open-ended image of this British artist whose work not only calls us to address historical and contemporary inequalities, but also allows us to imagine vastly different narratives and outcomes.

Theater of the Divine2019 is reminiscent of the Théâtre de l’Absurde, that crazy and sometimes nihilistic post-war dramatic movement characterized by playwrights such as Samuel Beckett and Jean Genet. However, in Himid’s hands, everything seems lighter and more hopeful.

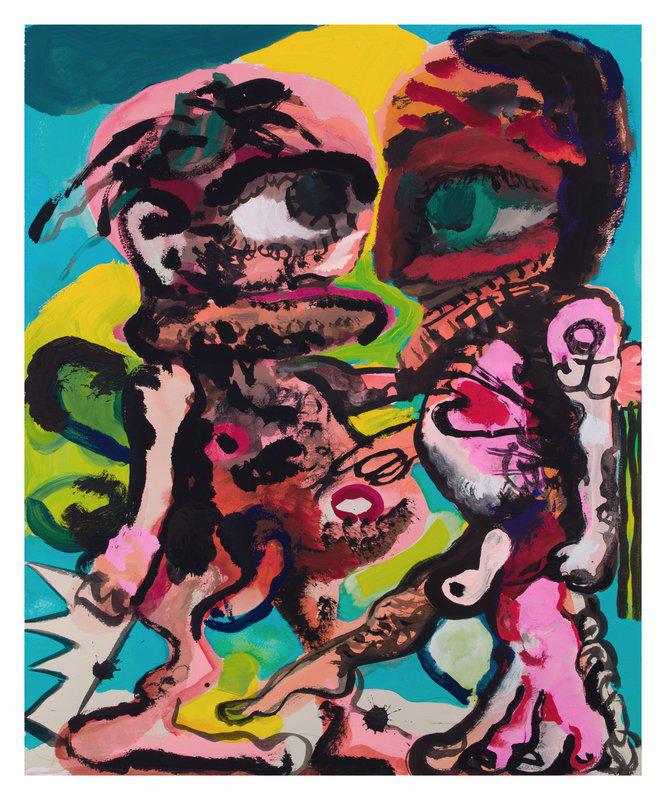

Dana Schutz– opponents, 2019

`

Which opponent has the upper hand in this image? It is not clear, just as the reasons for their antagonism remain murky. Maybe it should stay that way; In the work of this American painter, disorder is not a bug; it’s a feature. “A curious blend of playful, colorful humor and dark, morbid abjection, Schutz’s work references modernist styles such as expressionism and cubism alongside cartoon language and image distortion. in the digital age”, explains the text of Phaidon’s book, great female artists. “Atrocious, ridiculous, or impossible acts are often rendered with energetic painterly joy.”

Ebony G. Patterson – Untitled (Among the weeds, backpack, shoes and pebbles)2015/2018

What happened to the owner of the backpack, clothes and shoes in this work? Patterson takes us on with a beautiful alluring mix of florals and patterns, before presenting us with something that looks like a crime scene, or at least a visual missing persons report.

In her work, we are invited to see beyond the facades created by the “fabricated fantasies of a consumer culture and instead consider the realities of those who are “untouched by glitter and gold”.

It’s hard to deny the beauty of this work by the Jamaican-born artist, just as it’s nearly impossible to avoid darker meditations on still bodies, murder, and racial injustice.

Comments are closed.