For California Uyghurs, the Winter Games are a slap in the face

With a cheerful smile, cross-country skier Dinigeer Yilamujiang grabbed the Olympic torch with fellow Chinese Zhao Jiawen and lit the cauldron for the opening of the 2022 Winter Olympics on February 4, projecting an image of harmonious coexistence between Chinese ethnic groups.

More than 6,000 miles away in Southern California, Erkin Sidick called the stunt act.

Like Yilamujiang, Sidick hails from Xinjiang, a region in northwest China home to the Uyghur people, a Turkish ethnic minority who have been oppressed and displaced by the Han Chinese majority. Sidick couldn’t bring himself to watch the opening ceremony. The students he mentored in Xinjiang disappeared, and he cut off contact with his siblings there to protect them as the Chinese government cracked down and incarcerated the Uyghur community there.

But from his home in Santa Clarita, he read news about the torch lighter which state media said was of Uyghur origin. And he was struck by one detail in the footage of his family cheering him on from Xinjiang: no men were present.

“You know why?” asked Sidick, founder and president of the Uyghur Projects Foundation, a nonprofit organization based in Southern California. “Because the men are in concentration camps.”

Erkin Sidick, founder and chairman of the non-profit Uyghur Projects Foundation, said he was disappointed to learn that the Winter Olympics would be held in Beijing despite human rights abuses by the Chinese government. against the Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities.

(Dilnare Erkin)

For years, members of America’s Uyghur community — which numbers between 8,000 and 10,000, of whom about 1,000 live in Southern California — have advocated for the world to act against human rights abuses in Xinjiang. For many, the International Olympic Committee’s decision to award this year’s Winter Olympics to China felt like a slap in the face.

“It’s absolutely shameful,” said Bugra Arkin, 30, who runs a Uyghur restaurant in Alhambra. “The spirit of the Olympics is to bring peace and unite people, but it’s taking place in a country that is committing genocide.”

Arkin has not heard from his father, who lives in Xinjiang, since he was arrested by authorities four years ago and placed in what Arkin calls a “prison camp”. He does not know how long his father will be captive.

For nearly five years, the international community has observed authorities in northwest China detaining Uyghurs, a predominantly Muslim people embroiled in a large-scale social engineering campaign aimed at replacing their identity with a secular Chinese identity. .

A The United Nations committee said in 2018 that he had received credible information that at least 2 million Uyghurs and other predominantly Muslim minorities were being held in “political indoctrination camps” in Xinjiang. Sidick says the total number of Uighurs detained is much higher, potentially up to 9 million.

“The situation is awful. Horrible,” said Sidick, 63, senior optical engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge. “But the world doesn’t want to talk about it.”

Chinese authorities have said the detention centers are a “counter-terrorism” strategy adopted because of past riots and Uyghur attacks in the region. The unrest, some claimed by a separatist movement, came in response to the crackdown resulting from the state-sponsored migration of Han Chinese settlers into the Uyghur region.

But the vast majority of those in the camps have no ties to extremist or separatist movements.

In response to human rights concerns, the United States, Australia, Britain, Canada and other countries have refused to send government officials to the Games. For many Uyghurs, the diplomatic boycott was not enough. The Games went ahead and sponsors continued to advertise, even as human rights groups appeals to major Olympic sponsors to abandon their support or condemn the Chinese government’s persecution.

Neither Airbnb, Alibaba, Allianz, Bridgestone, Coca-Cola, Panasonic, P&G, Samsung, Toyota nor Visa responded to a Times request for comment ahead of the Olympics on what the companies thought about sponsoring those Games or whether they had changed one of their publicity projects. Intel declined to comment.

Atos said in a statement that it was not commenting on matters other than its role as global information technology partner for the Olympic and Paralympic Games and that the company is enabling digital technology for the Games “wherever they are.” unfold”.

Omega said in a statement that during its 90 years as official timekeeper of the Games, its policy was “not to become involved in certain political matters as this would not further the cause of sport in which our commitment”.

These Olympics present a dilemma for marketers, said Angeline Close Scheinbaum, professor of sports marketing at Clemson University.

The Games provide opportunities to uphold human rights, but commercially an Olympic sponsorship is ‘traditionally prestigious’ and a chance to uphold the Olympic ideals of friendship, respect and equality across world. And these two considerations do not always correspond to consumers who watch only to be entertained.

The sponsors were unlikely to change their plans, especially because the Tokyo Summer Olympics took place less than a year ago. This has given sponsors minimal time to adjust their marketing plans, said a sports marketing consultant who advises properties and countries around the world investing in sports and entertainment.

And quitting would only hurt athletes, said the consultant, who asked not to be identified.

“It’s about supporting athletes in 206 countries,” the consultant said. “It’s not necessarily about supporting the Games in a particular country.”

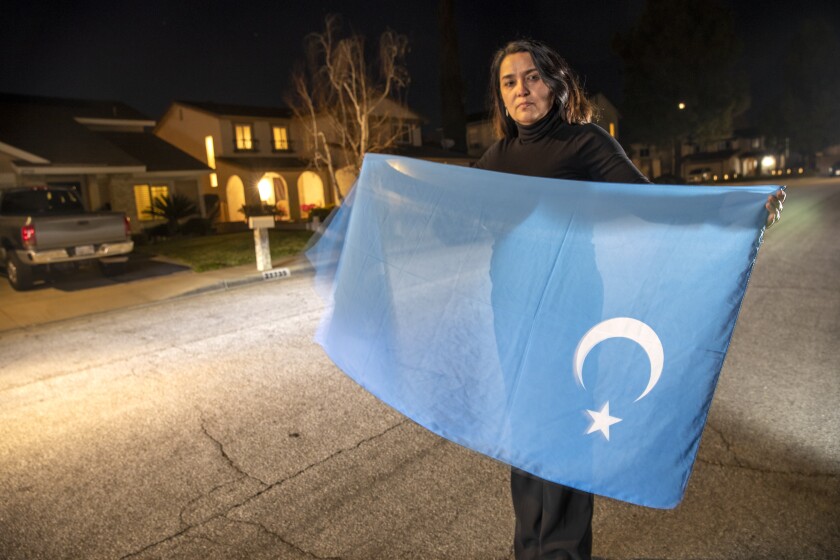

Nurnisa Kurban of Santa Clarita holds a scarf designed as the unofficial flag of Xinjiang, a region in northwest China that is home to the Uyghur people.

(Mel Melcon/Los Angeles Times)

Beijing hosted the Summer Olympics in 2008. At that time, fewer people in the general public were aware of the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uyghur community, although there were signs of discrimination, such as signage of Chinese-language signs in hotels that warned against renting to Uyghurs, said James Millward, author of “Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang.”

The 2008 Olympics were portrayed as a “big party”, he said, during which much of the international community focused on new buildings and a “China takes on its own” narrative. senses”.

Given the current international attention on the treatment of the Uyghur people, Millward was not surprised to see Yilamujiang included in this year’s opening ceremony. The 20-year-old cross-country skier is a first Olympian and finished in 43rd place out of 65 competitors at the cross-country skiathon on the first day of the Games. After her run, she left without speaking to the journalistsaccording to the Wall Street Journal.

“It was used to make a point precisely about what the PRC wants to do to Uyghurs and other people in Xinjiang,” he said, using an abbreviation for the People’s Republic of China. “That everything is fine, that the policies are working and that the Uyghurs and the Han are cooperating well.”

Nurnisa Kurban of Santa Clarita recalled that activists mobilizing for the rights of Uyghurs and Tibetans demonstrated in the streets of San Francisco before the Beijing Olympics in 2008. Yet the Games went ahead anyway.

“Twelve years later, we’re still talking about the Winter Olympics,” said Kurban, 47, a board member of advocacy group Uyghur LA. “I really appreciate the diplomatic boycott, and I think it sends a message to the Chinese government that the world is watching, but what is the impact? Did that prevent the Olympics from being held there? »

For years, Kurban and other members of the Southern California Uyghur community have protested and spoken to elected officials and academic institutions about the incarceration, forced labor and cultural erasure of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. It’s a plea she makes after her day job as a high school principal.

“I really don’t know what to say,” she said. “I don’t know what else we have to present for these companies, for these governments.”

Kasim, 49, a northern California resident who did not want his last name used for fear of reprisals from the Chinese government, said that before immigrating to the United States, he believed that America would help his Uighur community. He now describes that thought as a “naive dream”.

“The US government won’t do anything until the people ask it to do something,” he said.

Kasim said he believed China wanted to host the Games to “show the world how happy, prosperous and open China is” and to “control the narrative” about the country.

“Watching sport is one of the best ways for dictatorships and oppressive governments to take advantage of it and try to make themselves look good through the one thing that brings people together,” said Irade Kashgary, member of the board of directors of the non-profit advocacy group Uyghur. American Assn.

The situation has put the athletes in a difficult position at the Games, a position some Uyghurs sympathize with.

“I don’t blame the athletes for going to the event,” said a 33-year-old Brentwood resident who did not want his name used to protect his family in Xinjiang. “It’s not their fault that it’s in Beijing. They have dedicated their entire lives to their craft, and for many of them, this is their only chance to shine.

Instead, he blames the IOC and corporate sponsors for putting athletes in this situation. Although he is an Olympics fan and an avid skier and snowboarder, he was not going to watch the Games, which will end this weekend.

“I don’t think I have the stomach to watch it,” he said.

Comments are closed.