Housing and the arts, a vicious circle – Bella Caledonia

Rosie Priest investigates the unsurprising (but overlooked) connection between: a city designed for tourists; a bankrupt art sector and a housing policy that pushes for social cleansing.

The proposed initiative to crack down on short-term rentals in the city of Edinburgh has been postponed. But what have the arts to do with it?

Well, it’s mainly leaders in the arts sector who are lobbying against rental reforms, with the chief executive of the Fringe Society saying the proposed planning guidance for short-term rentals in the city of Edinburgh were “draconian”. Overt pressure from the arts sector on the council and government has led to delays in proceedings that would dramatically reduce poverty and curb preventable deaths of homeless residents.

This week, I wrote to arts organizations, their boards and staff asking for clarification of their actions: for that, I must apologize. While board members and executives are accountable for the actions of the organization, staff are not. In anger and frustration my actions were not motivated by care, I am fortunate to know many people who work in these organizations, and they continually work hard to bring about positive change in the sector and society . I am not envious of their immensely complex tasks. It is arts leaders who are lobbying against reform, not arts workers.

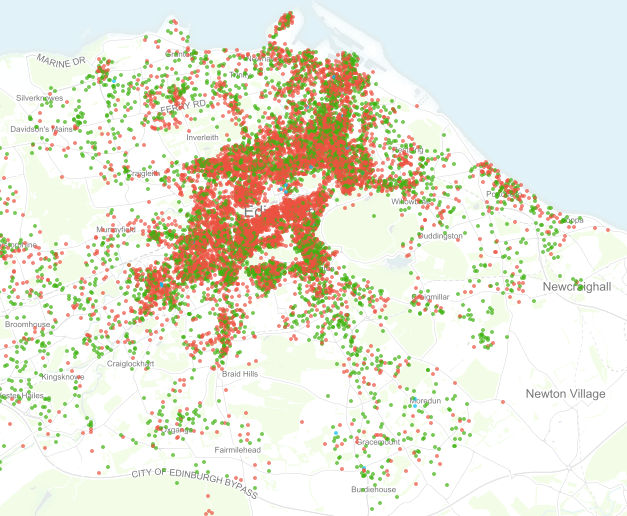

Of the nearly 8,000 short-term rentals available on AirBnB alone (Edinburgh has the highest per capita rates in the UK, with some areas of the city having 1 in 3 houses designated AirBnB), around 5,000 of these are entire homes, half of which are owned by owners with multiple properties (data on Edinburgh AirBnB can be found here). AirBnBs are empty an average of 277 days a year – mostly busy around August.

As general manager of the company complaints “The history of colocation during festivals goes back to its beginnings. The idea that it was going to become almost impossible would have been the final nail in the coffin” encourages a false narrative. Most rented homes are full properties, by owners with more than one property to rent. In fact the law States “For those renting a room or rooms in their own home, temporary licenses will be available, giving new hosts the flexibility and opportunity to try out a short-term rental before a full license application is made” , which points to either the chief executive of the Fringe society not fully understanding the regulations or willfully twisting the legislation to create panic and support its rejection.

“But why is it so important?” you may be thinking. Edinburgh’s commission on poverty said the need for affordable properties and access to homes in the city is the first factor of poverty in the city. Worryingly, Edinburgh residents who died homeless have increased by 150% in just 5 years. 44 Edinburgh residents died on its streets last year, while 5,000 homes stood empty. All of this is of course linked to the 5000 empty AirBnB accommodations in Edinburgh, as research shows an abundance of AirBnBs in a city drives up housing costs and increases poverty and homelessness.

from 2019

The active defense by the arts sector of the disappearance of legislation aggravates poverty in the city. I doubt the friends and families of the 44 homeless residents who lost their lives in the city would care if the city lost its claim to be a “capital of culture”, nor the 3000 families while waiting for HLMs or 2400 households who are currently homeless in the city. And as these statistics show, homelessness will only increase. There are many undocumented people like homeless taking extreme measures to stay warm this winter. Landlords responsible for the 5,000 homes that are empty for 277 days of the year, half of which are run by timeshare owners, enjoy the party leading up to the very literal deaths of the townspeople.

Some have argued that legislation needs to be explored further to account for impacts on the city, such as reduced accommodation for performers and audiences during the festival period in August. The organizations say the new legislation will have adverse effects on Edinburgh’s economy. However, what is not discussed is the extremely positive economic impact of the legislation. If the 5000 entire houses that remain empty for 277 days of the year become available, it is potentially thousands of residents who contribute to the economy of the city all year round. Hypothetically, if 2 people lived in each of these long-term homes and only contributed £10 a week to the city through takeaway coffees or trips to the cinema, that’s over £5million a year paid into the town. Many of the arts organizations that championed the disappearance of the legislation could benefit from residents with safe and secure homes, and they could become year-round audiences and participants. In fact, as we know that artistic workers earn less and feel less valued than many other workers in different sectors. Improved housing in Edinburgh could benefit many of the arts workers who are struggling the most in the sector.

When you think of the shocking closure of the Edinburgh cinema, a city with 10,000 additional residents living in safe, secure, long-term, non-poverty, non-poverty housing, could have benefited this arts institution? In fact, to what extent would festivals and arts organizations more generally have an interest in having residents occupy these empty houses year-round? Most festival goers are Edinburgh residents themselves, surely these numbers would increase if the legislation were passed? These are all hypothetical situations, but what we know as fact is that a high number of AirBnBs in a city increases poverty and housing insecurity.

If the arts leaders try to reduce legislation that will reduce poverty and improve the lives of the people of Edinburgh, they are showing violence against the people of this city. And even worse, they wield this violence on the people of this beautiful and vibrant city who have the least, many of whom their own organizations try to work with through ‘outreach’ interventions and ‘community’ projects.

I’ve written it several times: but this city is not a festival, it’s a house. Please can we as a sector push together for positive change that will first lead to poverty reduction and then understand how festivals work around this?

Comments are closed.