In Death, Kevin Johnson’s story becomes a cautionary tale for at-risk youth | St. Louis Metro News | Saint Louis

Demetrius Evans knew one thing after pointing a gun at a police officer’s head – that what he did next would change his entire life.

An officer had just found him cowering behind a trash can after Evans, 27 at the time, tried to evade police during a car chase. He had been “on the run” for nine months after missing a court hearing. With his criminal history and the police on his tail, he feared he would have to spend the rest of his life in prison.

He started to cry when the officer pointed his gun and shouted, “Put your hands on the wall!” Evans complied, but when the officer reached out to holster his gun, Evans jumped up to steal the officer’s gun. He pointed it at the officer’s head as a police dog bit his ankles.

Three more police arrived. Evans remembers them saying, “Forget it! You are a dead man!”

At that moment, Evans weighed what to do next. He was “already ready to die,” Evans recalled in an interview 26 years later. For him, death was preferable to life in prison, and he believed that killing or threatening to kill this officer would be the ticket out.

But then he thought of his unborn daughter, who was due in six months.

“‘I want to see my child,'” Evans recalled thinking. “‘I don’t want her to be like me and not know her father.'”

So Evans dropped the gun and was beaten by the police. He ended up with a 10-year prison sentence but was released in 2002.

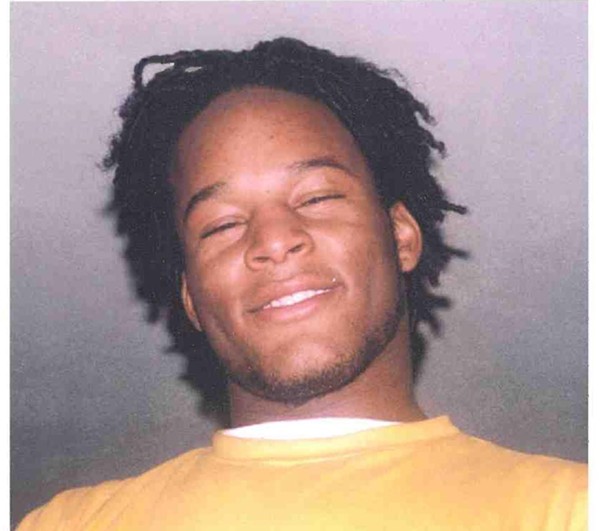

Monica Obradovic

Demetrius Evans poses for a portrait outside the St. Louis County Juvenile Detention Center.

Since then, Evans has dedicated her life to mentoring at-risk youth. In 2017, he founded Sudden Impact ICU, a non-profit organization providing resources to at-risk youth to help them turn their lives around.

More recently, Evans has turned to teaching children at the St. Louis County Juvenile Detention Center how to make good choices during times of high stress. He uses his own life as an example – and also the life of Kevin Johnson.

Missouri executed Johnson on November 29 for the murder of Officer William McEntee in Kirkwood. Like Evans, Johnson was wanted by police on the day of his crime. On July 5, 2005, Johnson’s 12-year-old brother Joseph “Bam Bam” Long died during a police search for Johnson. Johnson blamed McEntee for his brother’s death and killed him hours later.

Whether Johnson’s killing of McEntee was spontaneous or premeditated was debated during his trials, but Johnson has always claimed he acted on impulse. In an interview before his executionJohnson said he didn’t think he “didn’t even know why the shooting happened.”

Still alive and free today, Evans knows how close he was to ending up like Johnson. Prior to Johnson’s death, Evans and Johnson’s former mentor, Pamela Stanfield, obtained his permission to use his life story as a cautionary tale for youths at the St. Louis on what happens if you don’t think before you act.

“It is with me in mind that I speak here today,” Evans said. “They [the police] I had every right to punch myself, but because I dropped the gun and hit the jackpot, I’m here to talk to the kids now.

Stanfield’s relationship with Johnson began after his arrest in 2005. She met Johnson when she was principal of his school at Westchester Elementary in Kirkwood, but their friendship didn’t develop until she was 19. and locked up in St. Louis County Jail for McEntee’s murder. . Stanfield visited Johnson and helped him publish two books about his youth and his time in prison. A third book is in preparation on his last days.

Stanfield and Evans began teaching their program, called Split Second Decisions, three months ago. Prior to Johnson’s death, Stanfield relayed all the legal moves of Johnson’s case up to his death and what it was like to witness his execution.

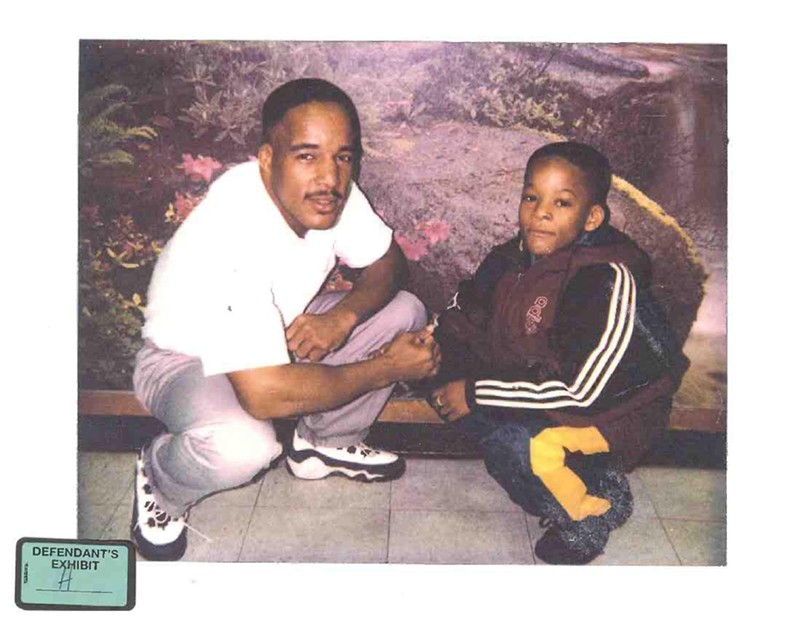

Courtesy of Pamela Stanfield

From right: Pamela Stanfield, Kevin Johnson and Johnson’s daughter, Khorry Ramey.

“You just pray that it’s real for them, because it could change their lives,” Stanfield says.

The kids wanted to hear Johnson’s story, Stanfield said, and they wanted to hear his words.

As an older white woman, Stanfield admits her words may not have much power for the male teens in the juvenile detention center, especially the black teens. So Stanfield read Johnson’s words to the children from the emails he sent her. Johnson wrote about his regrets and how he would do “a lot of things differently.”

“I would choose not to carry a weapon,” Johnson wrote. “It’s first because, as you’ve probably heard, ‘guns don’t kill people, people kill people’… Since my incarceration, I’ve learned to think before to act or react.”

Having a masculine voice of wisdom is something Evans says he wished he had growing up.

Evans spent much of her childhood at the St. Louis County Juvenile Detention Center. At age seven, he began running away from home (once, in an attempt to find his father). He got in trouble for stealing from grocery stores and taking money from gas station ledgers.

By age 10, Evans says he had been in the county juvenile detention center 22 times.

From age 7 to 10, Evans says he was locked up with Kevin Johnson’s father, Kevin Johnson Sr., who was about five years older than Evans and protected him. “He taught me how to fight in that,” Evans says.

Now 53, Evans devotes most of his energy to helping young people. After his last incarceration ended in 2002, he began sneaking into the county’s juvenile detention center, with the help of officers who knew him, to mentor children. His role as an unofficial volunteer eventually became legitimate. He is now an assistant juvenile detention officer.

The Split Second Decisions program he co-teaches with Stanfield has apparently already made a difference. In written statements provided by Stanfield, the children shared what they learned from Evans and Johnson.

“Talking about Kevin made me want to think before I do something, or take some time in your head to think, ‘If I do this, what’s going to happen to me or my family and my friends,” the 15-year-old wrote.

“It meant a lot to me and I need to stop being impulsive and think before I do something,” the 16-year-old wrote. “I find it difficult to control my anger. It makes me want to keep working. »

“I’m trying to find myself,” wrote a 17-year-old. “This lesson taught me a lot. I want to improve myself sometimes. I do not think so. But this lesson made me think about a lot of things.

Another teenager said Johnson’s story helped him see life “from a different perspective”.

“I’m 18 and had my first son at 17,” he wrote. “Hear his [Johnson’s] The story is sad and scary because he had a family he had to leave. Everyday I think about my son and how I can’t be with him and it hurts me, really… It’s not my life. Sometimes I want to give up but I can’t. My life is in the hands of God. Everything I do now is for my son.

A few weeks after Johnson’s death, Stanfield tells him that “it’s not real yet”.

Stanfield knows Johnson is gone. She remembers the blur of her funeral, her body in a coffin – the slight smile on Johnson’s face, the way she touched his shoulder. Still, the reality of Johnson’s death has yet to be fully established, she says. It was normal for them to write to each other every few weeks, so gaps in their communication are not abnormal.

“It probably won’t register until all of a sudden my brain says, ‘You haven’t heard from Kevin in forever,'” Stanfield says.

In a way, Johnson lives in his words. Stanfield still has his writings from the last 97 days of his life. Johnson tried to write about his final days in diary-like entries.

Stanfield has yet to collect all of her latest passages into a book, but she did notice a passage in which Johnson wrote about a conversation the two men had about guns.

“How can you tell a kid from a tough neighborhood to put down his gun when everyone else has one?” Stanfield asked Johnson in the passage. Johnson wrote that he struggled to come up with an answer. He struggled with guilt over his brother’s death – and regret over owning a gun.

After that conversation, Johnson wrote that he “deeply hopes that young people can learn from my story and leave the guns where they found them so they can live long and prosperous lives.”

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | instagram | Facebook | Twitter

Comments are closed.