Inside Housing – Insight – The new social housing: data shows scale of toddlers in temporary accommodation

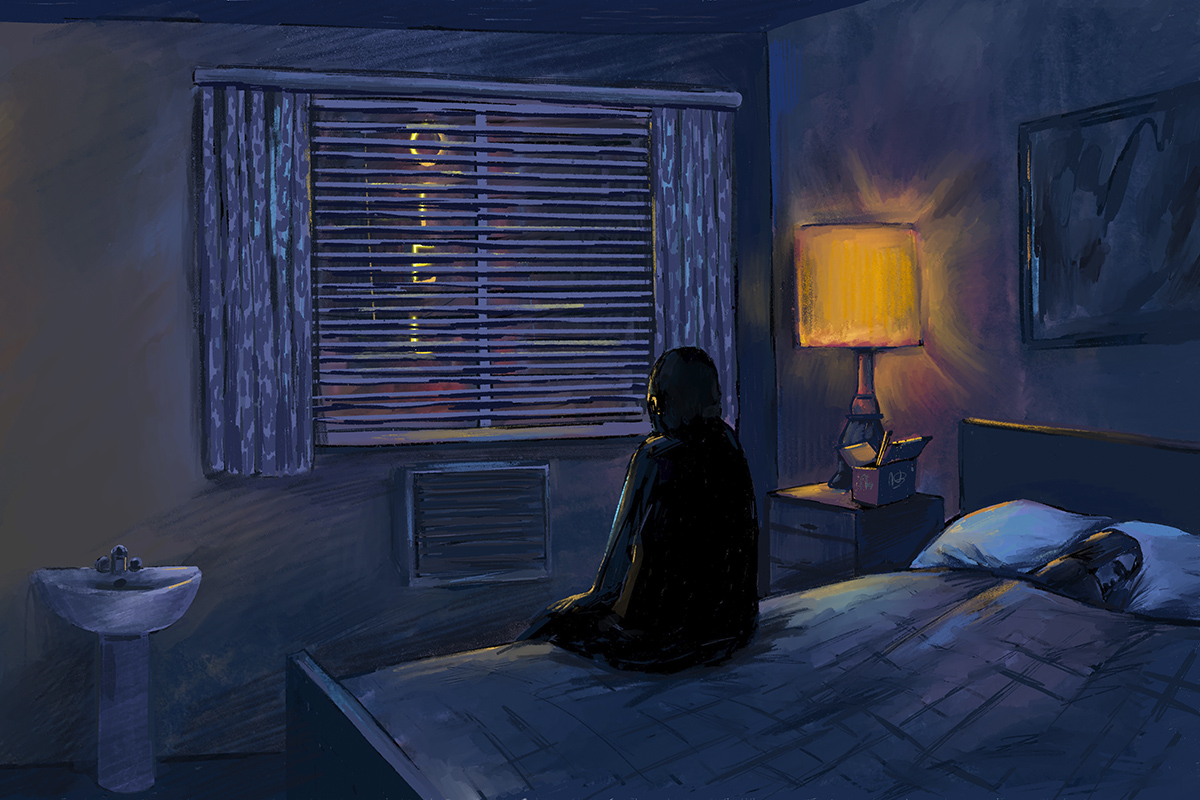

“For families with kids under five, it’s really tough on parents,” says Deborah Garvie, policy manager at Shelter. “Once they drop off their children at seven o’clock in the evening, they have nowhere to go. Some of them just sit there with the lights off all evening.

“A lot of our mums go to the doctor and say they can’t sleep,” says Ms Williams. “And either the doctors say there’s nothing you can do about it, all you need is a house, or they say there’s sleeping pills.

“But it’s not a mental health issue not being able to bear what is unbearable. It’s a proportionate response to what’s going on, but since there’s no way out, they’re medicalized with antidepressants and sleeping pills.

The reasons we have come to this position are frustratingly simple. There is a chronic lack of social rental housing, which has not been built in large numbers this decade for the first time since World War II, at the same time as tens of thousands of existing properties have been demolished or sold.

“A lot of this is down to the massive housing shortage, due to the lack of construction of truly affordable housing. We have seen the number of households able to move into social housing decline massively. And that has led to a huge increase in the number of people stuck in temporary accommodation for a very long time,” says Ruth Jacob, policy officer at the homelessness charity Crisis.

Soaring rents

At the same time, the allowance system was suffocated. The Local Housing Allowance (LHA) (the amount that can be claimed by a household in the private rental sector) was capped at a maximum of the 30th percentile of local rents and then frozen, meaning there are swathes of of the country where there is not a detached house available for a family that cannot afford to pay market rates. As rents soar, this problem becomes more acute.

“What we hear is councils finding it impossible to find accommodation to move to,” says Ms Jacob. “There has been a huge drop in the affordability of the private rental sector. The LHA rate that people can get has remained frozen but rents have increased massively.

Short-term rentals like Airbnb have compounded this problem, cannibalizing an already overheated market.

“Basically, temporary accommodation is the new social housing. This is where you end up if you can’t afford the market and the state welcomes you”

“We have tourists sleeping in houses built for families and families sleeping in hotels built for tourists,” says Ms Williams.

“Basically, temporary accommodation is the new social housing. This is where you end up if you can’t afford the deal and the state takes you in. It used to be social housing, but now it’s temporary housing,” says Ms. Garvie.

The answers are as simple as the causes of the problem. We need more social housing and a benefit system that enables people to access housing and maintain their tenancy.

If the government is loath to spend money on it, it should factor in the costs of temporary housing – where local authorities drive up bills overnight, shifting the state’s huge wealth into the hands of some of the most exploitative landlords in the country. Recent research by Shelter showed the annual bill to be £1.6billion.

“It’s the crazy temporary housing economy,” says Ms Garvie. “It created a crisis-driven market. The local authorities have families with suitcases that they need to find accommodation for and they are doing their best, but it is really an impossible situation for them.

It is important, however, that if this crisis is addressed, it is addressed in the right way. Marc Francis, adviser to Westminster-based charity Z2K, points out that a simple target to reduce the number of families in temporary accommodation could have the wrong impact.

Under the Localism Act, councils have the power to ‘fulfil’ their duty to a family by providing them with private rental accommodation, sometimes several miles from their place of residence and inappropriate to their needs. If they refuse it, they risk losing access to any help. “We often see this sword hanging over families,” he says. “A simple push to downsize isn’t always good for households.”

Nevertheless, it is clear that change is overdue. “How is this not considered a disaster? If a river burst its banks and rendered 30 people homeless, it would be considered a disaster. But that’s exactly what’s happening every week in this borough because of the housing market,” says Ms. Williams.

Disaster seems to be the right word. And that – like too many of those we face now – is man-made.

Comments are closed.