How Airbnb and Uber use militant tactics that disguise their corporate lobbying as grassroots campaigns

What David Cameron once called “the all too comfortable relationship between politics, government, business and money”, has been in the public eye through his own lobbying on behalf of former billionaire Lex Greensill’s influential financial firm. The former British Prime Minister predicted that lobbying would be “the next big scandal” after parliamentary spending. He was proved right.

Nathan King/Alamy

With Prime Minister Boris Johnson call an inquiry in the episodeAll this raises questions about the lobbying laws set up by the Cameron government in 2014. They seem so weak that it seems that nothing in the current saga was illegal.

Exemptions in the rules that prevent in-house lobbyists like Cameron from having to appear on the statutory register have left up to 80% corporate lobbying intact.

Yet this is not the only aspect of corporate lobbying that should concern us. Recent practices among companies in the digital economy such as Uber and Airbnb illustrate that many activities contrary to Transparency International’s guidelines for ethical lobbying can take place without breaching any of the existing UK rules.

“People’s Lobbying”

In addition to traditional lobbying, these digital platforms have cultivated corporate “grassroots lobbying” initiatives in which they resource and mobilize their users to push for deregulation or to block government proposals or sanctions. To do so, they use civil society practices such as online petitions addressed to politicians, individual meetings with representatives, protests and partnerships with existing civil society groups.

My recent report in association with the Ethical Consumer Research Association explore this. Airbnbthe main case study, has hired hundreds of “community organizerssince 2014 to create more than 400 seemingly independent associations of owners, mainly in Europe and North America but on all seven continents. The society provides members of these so-called roommate clubs (sometimes also referred to as host clubs) with political training, refreshments, and room rental for meetings, as well as transportation, editing and rehearsal of owner testimonials, and suggestion of political goals the company desires .

Airbnb clubs do not track inclusive approach to the countryside which is common in the tradition of community organization from which they draw their inspiration. Former staff members describe how they have organized clubs of individuals or small businesses that rent properties on the platform, rather than the business owners who tend to hold the majority of registrations and who have been of greatest concern to activists and policy makers.

Airbnb says the clubs exist to allow owners to “build new relationships” and “discuss issues in their communities and help each other find more information about local rules”. Yet our research found that clubs are funded and coordinated by Airbnb around its regulatory goals. They are particularly concentrated in cities where the company faces the greatest challenges, such as Barcelona, Berlin, Edinburgh, New York and San Francisco.

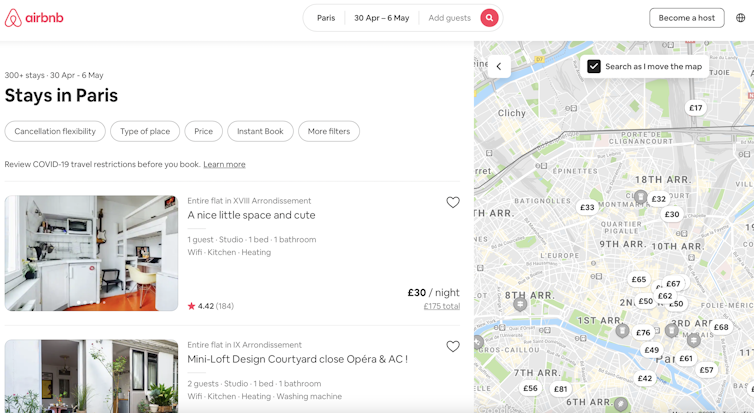

In Paris, for example, a former employee said that Airbnb intended to create a club in each arrondissement, after facing proposals to force landlords to register short-term rentals with the authorities. Here and elsewhere, local governments and anti-poverty activists concerns tend to revolve around housing, with short-term rentals tied to rising rents and long-term residents being forced out of neighborhoods.

Airbnb

Other platform companies also routinely engage users and staff, though few examples seem as elaborate as Airbnb’s approach. For example, in November 2017, a widely promoted campaign #SaveYourUber Petition was directed at London Mayor Sadiq Khan after the London Transport Authority refused to renew Uber’s safety license. It turned out to have been initiated by Uber’s British and Irish director, Tom Elvidge. This is a routine tactic for the company, which has created a large number of similar petitions internationally using a petition tool. Change.org.

Another example is electric scooter company Bird, which added a push-button notification to its app to encourage customers to flood local lawmakers in Santa Monica, California with support emails. It was on the back of a criminal complaint made by the town hall against the company in 2017.

Power of the platform?

Grassroots corporate-sponsored lobbying, sometimes referred to asastroturfis better known in the United States than in Europe. It is usually associated with the the tobacco, pharmaceutical and fossil fuels Industries.

The tactics used by platform companies such as Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Bird and delivery company Doordash, are similar to traditional astroturfing, but with key differences. Where astroturfing campaigns are usually initiated by public affairs consultancies, companies in the digital economy tend to hire in-house staff, with experience in organizing NGOs or campaigning for elections. As “in-house” lobbyists, they would not be subject to the UK Transparency Laws – just like David Cameron’s work for Greensill.

Another difference is that the platforms also seem to take advantage of their users’ data to mobilize their customers, owners or drivers – Airbnb telephones owners to encourage them to join roommate clubs, for example, falls into this category.

Civil society concerns

Corporate-sponsored grassroots lobbying is a growing concern for transparency campaigners such as Business Europe Observatorysupporter of the report, and Transparency International (TI), which specifically warns against “hidden and informal influence”. At the most extreme end, TI notes, this “includes acting through front organizations,” which are entities that act as the face of another organization. My report argues that this is how we should understand Airbnb’s relationship with its clubs.

charities such as Community organizers and many tenant unions are also concerned about this form of lobbying, especially when it thwarts community campaigns for the protection of affordable housing. Community organizers is worried that, “decision makers and customers will react as if this were a real grassroots campaign, rather than a corporate lobbying effort.” Former Airbnb employees share this concern.

I also question the legality and ethics of political use platform data. Few users, when contacted, are likely to be aware that they have consented to become recruitment targets for the corporate policy organization.

Lobbying regulations outside of Canada and some US states still say little about corporate-sponsored grassroots lobbying, so there is a risk that the practices will continue to grow unchecked. The problems with too narrow a definition of commercial influence become clear, whether in relation to internal lobbying like Cameron’s, or to these “grassroots” methods. A complete overhaul of the lobbying rules seems urgent.

We invited the digital companies in the article to respond to the report’s findings.

An Airbnb spokesperson replied:

We announced the creation of Host Clubs during a press conference in 2015. Host Clubs have always worked closely with our teams to defend the interests of the Airbnb community and we are extremely proud of this work.

A Doordash spokesperson said:

We know our Dasher community appreciates the flexibility to earn when and how they choose because they tell us that every day. This is exactly why we are committed to protecting these additional revenue opportunities, while continuing to work with state and federal lawmakers to combine Dasher independence with greater safety.

The other companies did not respond in time for publication.

Comments are closed.