Mark Zuckerberg’s Metaverse Vision Has a Fatal Design Flaw

Virtual real estate is booming. In December 2021, a buyer spent $450,000 on land in the virtual world of rapper Snoop Dogg. Which begs the question, what will be built there?

In the physical world, cities are shaped by countless forces. Some are desirable, designed in consultation with local communities. Others are not, subverting building regulations for financial gain.

In contrast, the space in the metaverse – the versions of internet including immersive games and other virtual reality environments – has so far been smooth, clean and very ordinary. This is despite its ties to emerging “disruptive” technologies, such as cryptocurrencies.

Our research shows that while designing virtual worlds gives people a creative voice, it can also reveal the infinitely more complex social, societal, and historical ways in which physical places are formed.

We explore how architects can use virtual environments to enhance understanding of real-world cities. Metaverse designers should also be aware of the social effect their designs will have.

People have always imagined cyberspace as a version of real urban space. In his 1992 novel, SnowfallAmerican science fiction writer Neal Stevenson was the first to imagine the metaverse, built along what he called the Rue. In its universe, this large boulevard goes around the globe but nevertheless presents itself as a typical urban artery, lined with buildings and electrical signs.

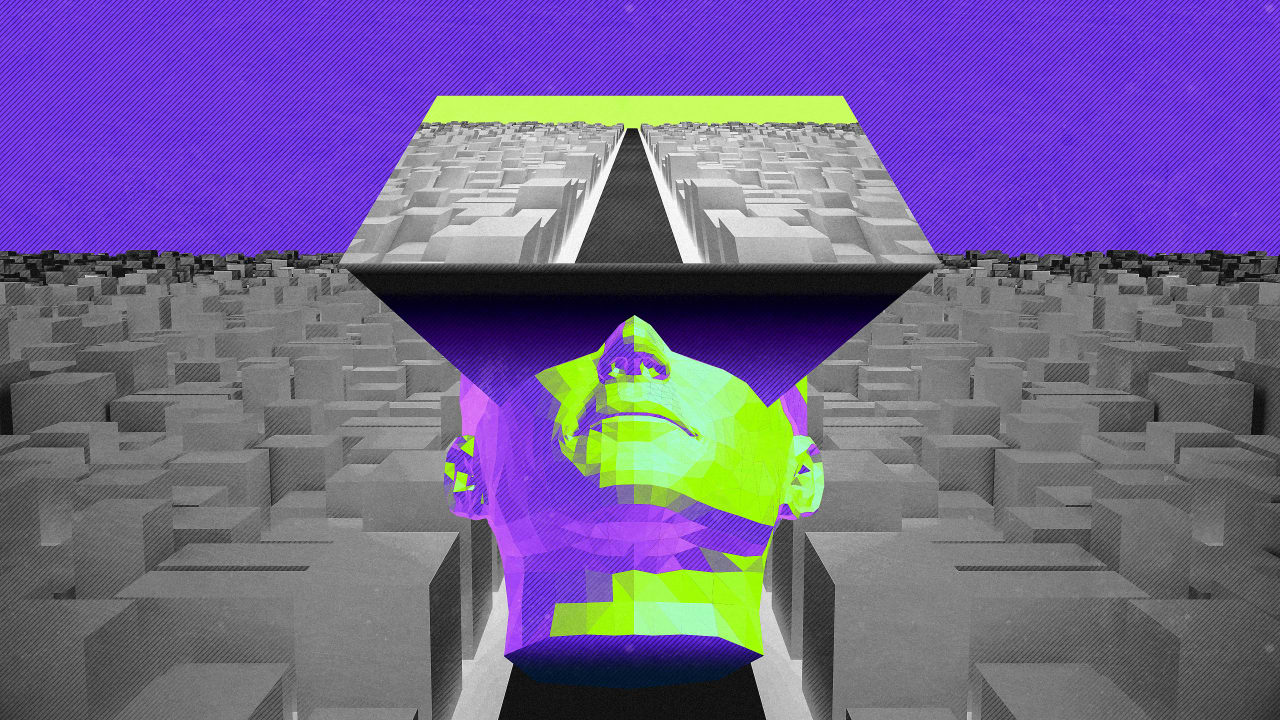

Recent ads from Facebook’s parent company Meta suggest that Mark Zuckerberg’s vision for the Metaverse isn’t much different. As a visitor, you find yourself faced with an impossible landscape where snow-covered forests meet tropical islands, but the structures built are minimalist villas and easy-to-clean space stations. It’s more like a spatial mood board of “cool looking” random images. Zuckerberg’s metaverse world acts more like a desktop background than a reflective spatial environment.

Meta’s Horizon Worlds is a social platform where users have a set of tools with which to create and share virtual worlds. Here, the ads feature avatars of users walking through food halls or sitting in dining cars, all designed to look like their real-world counterparts, but rendered in a simplistic graphic style, like a children’s TV show.

Practical (but unnecessary) design elements, including streetlights, power outlets, and window frames, emphasize the urban nature of these sterile, virtual spaces. It fits the generic global minimalism that American tech journalist Kyle Chayka named “airspace”: that ubiquitous aesthetic (wooden benches, exposed brickwork, industrial light fixtures) found in cafes, offices, and Airbnb apartments around the world.

Virtual urban planning

While Meta’s promotional vision for Metaverse worlds is a series of separate snapshots, other Metaverse platforms, such as Decentralized, The sandboxand Cryptovoxels, involve a certain level of town planning. Like many real-world cities, they use a grid system with plots of land spread out on a horizontal plane. This allows the property to be easily parceled out and sold. However, many of these parcels remained empty, demonstrating that they are mainly traded speculatively.

In some cases, content – buildings and things to do, see and buy within – has been added to plots, in an effort to create value. Virtual real estate developer, the Metaverse group is rental of decentralized plots and providing in-house architectural services to tenants. Its parent company, Tokens.com, also has a virtual headquarters there, a sci-fi-style block tower in an area called Crypto Valley. Like many other metaverse buildings, it serves as a giant space symbol, designed to draw people towards it.

Other Decentraland structures include a recreation of a dive bar by Miller Lite and a neon shrine promoting Japanese virtual diva Edo Lena. There are also countless white cube art galleries selling NFTs (digital certificates linked to works of art), such as the one at mlo.art. These structures look like real-world galleries, but simplified and decontextualized.

Referential architecture

In his 2012 book, Build imaginary worlds, media theorist Mark JP Wolf says fictional worlds “often use the primary world [i.e. real world] faults for many things, despite all the faults they can reset. In other words, since everything in the Metaverse is built from scratch, technically you don’t actually need to reference the real world in your designs.

But many people choose to do it anyway. They look for familiar architectural features in their virtual buildings, as this makes it easier for participants to feel immersed.

Research shows how this is also how artificial worlds have been created in real life. Art historian Karal Ann Marling describe the built environment of Disney theme parks as “comforting architecture” where reality is “pampered”; that is, raised in such a way that it feels both new and comfortably familiar.

Las Vegas is another place to find such “plussed” architecture. The Nevada city was describe by urban historians Hal Rothman and Mike Davis as a vast laboratory. Companies have created urban spaces there as collages of other cities, such as Paris and New York, with the aim of testing “all possible combinations of entertainment, games, mass media and leisure”.

Real towns now choose to mimic each other in the metaverse. South Korea Metaverse Center 120 will provide both recreational and administrative public services. The project is one of the few primarily government-led metaverse initiatives, under the new national digital pact for public digital infrastructure. The aim is to develop smart city technology, preserve and enhance heritage and host cultural festivals.

Studies show that the design of urban public spaces has evolved alongside the way people behave in them. Likewise, the success of the metaverse, whether people use it or not, will depend heavily on the environments created.

Virtual spaces should be convenient to access and appealing enough for them to come back to. They must also operate and expand what differentiates them from physical spaces. Simply transplanting the real-world logics of real estate development and commerce into the metaverse could recreate the social and economic stratification we find in real-world cities, undermining the emancipatory potential of the metaverse.

Luke Pearson is Associate Professor, Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL Faculty of Built Environment. Sandra Youkhana is a lecturer and doctoral student at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL Faculty of Built Environment. This article is republished from The conversation under Creative Commons license. Read it original article.

Comments are closed.