‘Working class’ reps say they can’t pay DC rents while earning $174,000 a year

When the federal government moved to Washington, D.C., in 1800, lawmakers complained about leaving rear Philadelphia’s many accommodations for the new capital’s limited stock of boarding houses and taverns.

Thus was established a tradition of politicians complaining about finding housing in DC, which continues to this day.

Among the upcoming 118th Congress are several freshman progressive representatives who say having to spend their $174,000 congressional salary on housing in the district is not just difficult, but a deliberate effort to keep them out of government.

“For those of us who are working class, this is another reminder that this place was not designed for people who truly represent their communities,” said freshman representative Delia Ramirez (D–Ill.) at The cup yesterday.

Ramirez — herself a landlord and landlord in her neighborhood — said DC’s housing costs are so high she’s had to scrap plans to rent an apartment on her own. Instead, she’s splitting the $3,000 rent on a Capitol Hill townhouse with another congresswoman.

Some 34% of DC households and 43% of renter households are took into consideration overwhelmed by costs, meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on housing. Ramirez is certainly luckier than that. According to the figures she gave The cup, she only pays 10% of her congressional salary for her DC housing.

The cup nevertheless claims that Ramirez “knows the struggle for housing”. Apparently she’s not the only one.

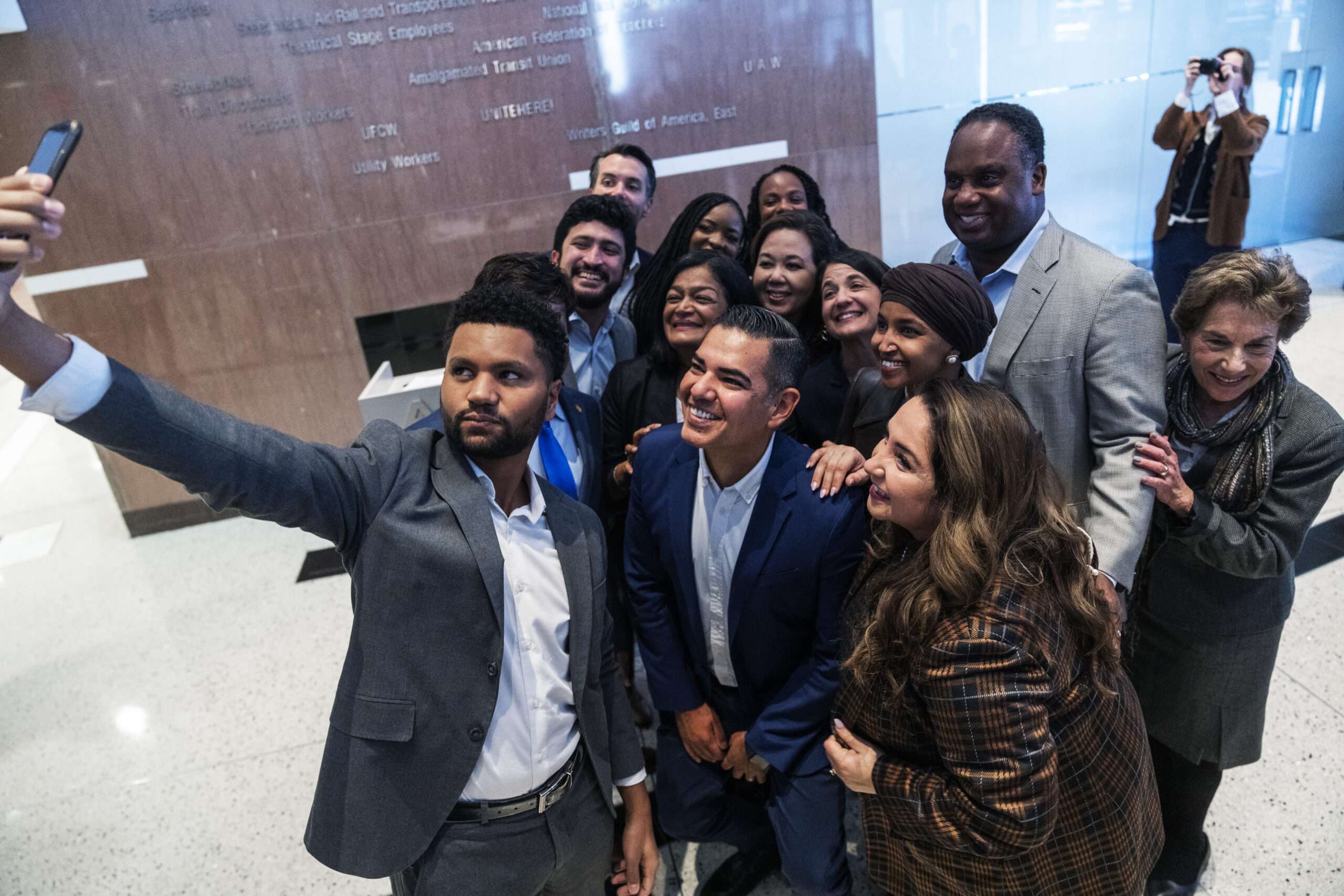

In December of last year, freshman Rep. Maxwell Alejandro Frost (D–Fla.), the nation’s first Gen Z congressman, got a lot of media attention when he said his bad credit would have cost him an apartment and application fees in the city. upscale Navy Yard neighborhood, adjacent to the Capitol.

“It’s not for people who don’t already have money,” he said. said on Twitter in December. He told the Washington Post he would try his luck with mom-and-pop landlords and, if need be, rely on couch-surfing or Airbnb until something more permanent materializes.

Frost’s fight earned her plenty of headlines and public sympathy from Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D–NY), who had also complained about her. alleged incapacityrepeated credulously in the press, to afford housing in DC when he was first elected in 2018.

“I went there”, she said on Twitter. “This is one of the many ways Congress structures itself to exclude and kick out the few working class people who *get* elected.”

None of these “working class” representatives have been forced out of office by DC’s admittedly high housing costs.

At most, they had to make do with accommodation that was a little less spacious, practical or solitary than they had hoped for. (Ocasio-Cortez doesn’t seem to have had to make such compromises. Free tag reports She’s housed in a luxury building at Navy Yard.)

In this light, the complaints of Ramirez, Frost and Ocasio-Cortez seem less than groundbreaking. We could even consider them as having rights. They certainly lack perspective.

All attempt to claim a working-class political identity while demanding that they be freed from having to make compromises in their life circumstances that even DC’s well-paid professionals must endure.

A need for space can mean sacrificing proximity to the office. Saving on rent can mean giving up the privacy of living alone. Sometimes when you move to a new city, you have to fill out multiple lease applications or rent an Airbnb for a while.

Members of Congress having to do this doesn’t seem like the biggest scandal in the world.

DC is indeed unaffordable for many people who earn well under $174,000 a year. Making the city more affordable for them would involve eliminating, or at least relaxing, zoning and height restrictions that limit the amount of new housing that can be built.

To their credit, Ocasio-Cortez and Frost call those “exclusion zoning” restrictions in their housing platforms. To their demerit, they propose rather heavy federal interventions to eliminate them. They also combine their zoning reform proposals with destructive nationwide rent control.

In truth, other than attaching certain conditions to federal grants, there is little the US Congress can do to reform state and local housing laws.

The only exception, of course, is DC

The district’s self-governing status means that Congress retains ultimate legislative authority over the city. If Frost, Ramirez and others really wanted to make their new home more affordable, they could introduce a bill eliminating the city’s zoning restrictions. They could introduce legislation repealing the city’s high Airbnb taxes, costing Frost a pretty penny while he searches for more permanent housing.

They might not solve all the problems of these first-year reps. Even if DC were transformed into a zoning-free YIMBY utopia, tenants would still have to submit to credit checks and compromise between having a yard and walking to work.

But a more affordable city means more working-class people could live alongside well-paid congressmen.

Comments are closed.