For Former Slaves, Taking the Name “Washington” Was Actually a Pretty Powerful Decision | Columns | Tampa

I recently became obsessed with George Washington’s teeth for seemingly random reasons. Once I delved deeper, I understood where my attraction was coming from – apparently the teeth in her mouth were from enslaved black people.

This intertwining of oppressor and oppressed is the entanglement we call ‘nation’. And no matter how hard we try to separate ourselves, we can’t. We are intrinsically connected, bound not by sentimentality but rather by consequential facts.

Otherwise, how would the so-called “founding fathers” have risen to revel in the glory of this title without the black people they enslaved? And yet, the unnamed often remains ignored even while living in the mouth of a slaver whose image has been immortalized in monuments and coins.

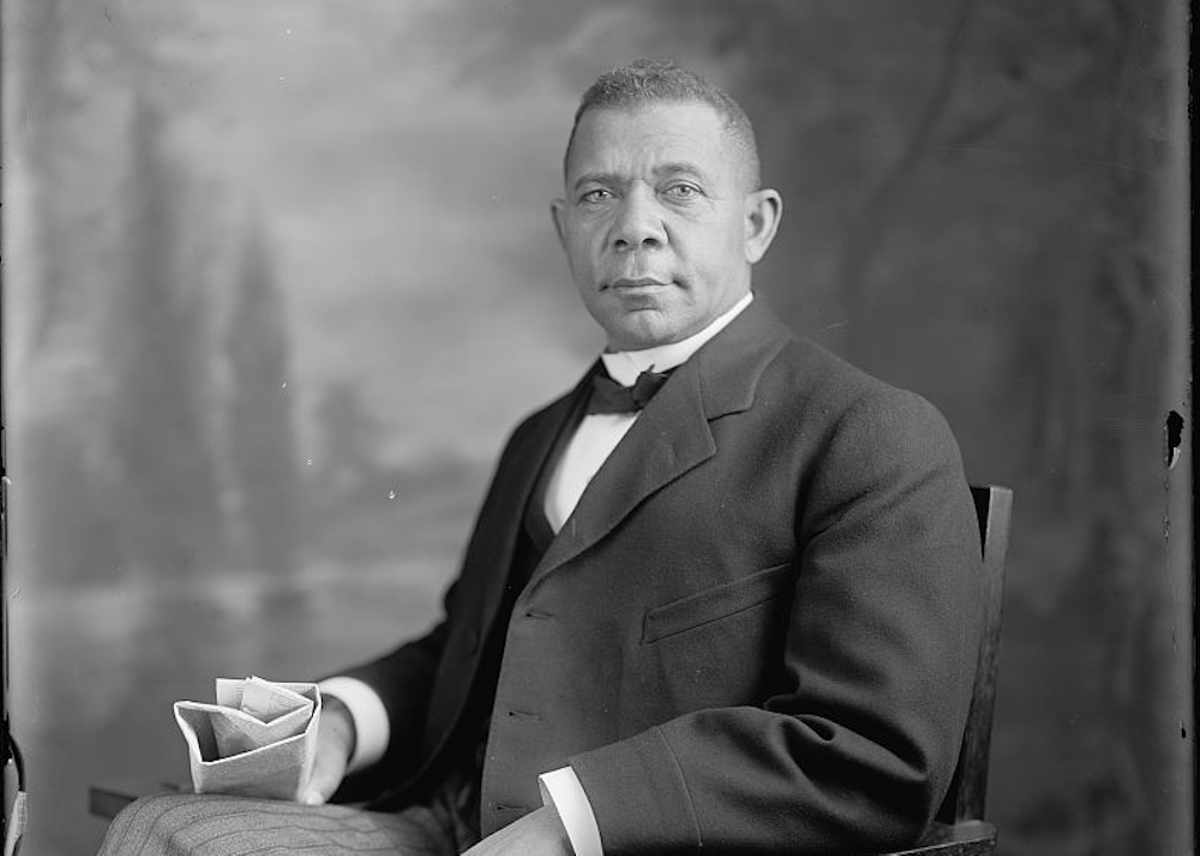

The power to name is indeed real and it seems that many former slaves understood this by choosing their surname before, during and after emancipation. Some chose their surnames based on their last master, others chose popular names associated with legitimacy and existing social capital. Regardless of the reasoning behind the surname selection, “Washington” has become “the blackest name in America” with more than 90% of those with this surname being of African descent.

It was actually quite a powerful move. By taking the literal name of the master in the eyes of white America – the oft-glorified founding father and America’s first president – once-enslaved black people set the stage to embrace their own future influence. It was a kind of symbolic recovery that came from having their own identity stripped away and beaten down. So when they were given the opportunity to decide what name they should pass on to their descendants, they knowingly and perhaps unknowingly made a cause to position themselves as important from a societal point of view after enduring the degrading atrocity of American slavery.

Another layer to this is the idea of who came first in the history of mankind. What we call “founding” is loosely based on a misconception that our civilization began with a white man and a white woman – in the case of our nation, it’s George and Martha Washington and in the case of the Western religious history is the idea of a white male Adam and a white female Eve. However, we do know that scientific evidence shows that the origin of human civilization, the original founders so to speak, came from Africa.

It’s poetic justice, in a way. The complicated relationship we have with each other in this nation is expressed vividly through the myths and facts surrounding Washington – the myth of George chopping down the cherry tree, the myth of his wooden teeth, and the reality of him. enslaving black people while serving as the leader of this nation. I saw these three components as being connected and so I linked them together in my poem. It’s about deconstructing the false narratives of our roots, especially those that have become infected and rotten, and giving space now to develop a true understanding of how we all got here.

Washington is the blackest name in America

We like to believe

our father’s teeth

are made from trees,

although in reality

what he held in his mouth

were the bones of these giants

of the homeland –It’s real wood

he shot on purpose,

with every bite

Eat

brown limbs

that finally

bear fruit and bloom.

Comments are closed.