Iceland plans restrictions on Airbnb amid tourism explosion | Iceland

Iceland is about to brake a Airbnb explosion as it attempts to balance record tourist numbers with the protection of its spectacular, unspoiled landscape and traditional way of life.

A bill, which could become law this week, aims to restrict the number of days residents can volunteer Airbnb rentals in their properties 90 days a year before they have to pay business tax.

The move comes as the island’s 335,000 residents are expected to welcome 1.6 million visitors this year – a 29% increase on last year – drawn to glaciers, fjords, lava fields, hot springs, hiking trails and the midnight sun.

It is part of a series of measures to control the rapid increase in visitor numbers, including game of thrones fans flock to the drama’s filming locations.

Tourism has been the salvation of the North Atlantic island where the economy, built on fishing, was badly damaged after the catastrophic collapse of its banking sector during the 2008 global recession.

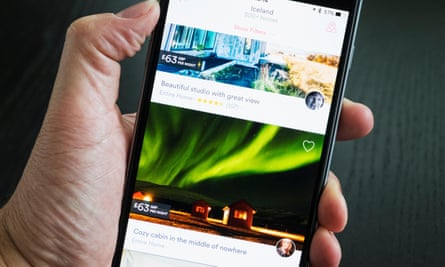

Now, as hotel construction struggles to keep pace with growing tourism, many Icelanders are making money through Airbnb and other short-term rental sites, especially in the center from Reykjavík, where the majority of tourists stay.

Report estimates 124% increase in Airbnb rentals in a year, with more than 100 apartments available on the capital’s main street alone. The result has been a dramatic increase in housing prices in central Reykjavík and a shortage of long-term rentals.

Elvar Orri Hreinsson, research analyst at Íslandsbanki who recently produced a report on the impact of tourism in Iceland, said the ratio of short-term vacation rentals to properties in the central capital was “really high” by compared to other more populous countries.

A thousand new hotel rooms were needed this year, but only 300 were planned, he said.

“We are only building 30% of what we need in the capital region,” he said, making it impossible to keep pace. But he cautioned against “following growth at this rate”.

Tourism now accounts for 34% of Iceland’s export earnings, down from 18% in 2010. So, Hreinsson said, the economy would be hit harder now by a setback such as a volcanic eruption, than it would be. was after the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in 2010. .

In April, the Supreme Court ruled that anyone in a building must get permission from other residents before renting their apartment through Airbnb. Two city councils, Kirkjubæjarklaustur and Vík í Mýrdal, have already put in place measures to restrict short-term tourist accommodation. The latter would have rooms for 1,300 guests, but a population of only 540.

The new law, which is in the final stages of review, would apply to all of Iceland. Ashildur Bragadóttir, director of Visit Reykjavíksaid she was pretty confident it would be passed “because everyone sees that something has to change. We don’t want downtown Reykjavík to be just touristy, with no people”.

Local media reported complaints that “puffin shops” – those aimed at tourists – and Viking-themed businesses were taking over downtown Reykjavík.

Ólöf Ýrr Atladóttir, the director of Icelandic Tourist Board, said there were “some challenges, but not strong tensions”, and recent research showed that Icelanders were positive towards visitors and tourism itself, despite some concerns. But, she says, “we have to watch [it] very closely and take care not to create, for example, a city center empty of citizens”.

She said the legislation was not an attempt to ban Airbnb, as many tourists preferred the experience to hotels, but to establish controls and “give it a place within the [tourism] sector where he must respect rules”.

Insufficient infrastructure has also led to tensions between residents and visitors, particularly due to the lack of public toilets and parking at the most popular sites, including Gullfoss waterfall, Geysir geothermal spring and the national park. of Þingvellir. Tourists have been accused of urinating and defecate on the graves of famous Icelandic poetsand drive off-road rental cars through fragile protected sites.

Gunnar þór Jóhannesson, associate professor of geography and tourism at the University of Iceland, said the lack of infrastructure was a challenge. With Keflavík as its only airport of entry, Iceland “was struggling to distribute its tourists across the island”. Some hotspots were under pressure in high season, and there were fears that “downtown was emptying out, becoming sort of Disneyfied.”

A cap on the number of tourists on the most popular hiking trails, such as the Laugavegur, could be an option, he said, but a cap would not work for towns or the city. “We’re not there yet and I don’t think that’s the right way to go.”

The government plans to introduce direct international flights to Egilsstaðir in the east and Akureyri in the north, which Atladottír says would help equalize visitor numbers across the country throughout the year and make the areas less visited island more accessible, especially during the winter months.

Platforms, barriers and pathways could help increase the number of visitors to key sites and protect them at the same time, Johannesson said.

“We have to be careful not to go too fast, and we have to have the time and space to gather the information and data we need to make the best decision possible.

“It’s easy to paint a rather gloomy picture of what’s going on because it’s happened so fast that Iceland is overwhelmed with tourists. But it doesn’t have to be that way. It’s a huge challenge, and in all honesty, the government is now trying to take matters into its own hands,” he said. “These are growing pains.

Comments are closed.