Why I would rather take a free couchsurfer than earn money with Airbnb | Australia Travel Blog

I recently realized that travelers to Melbourne have two options if they want to stay with me. They can find my Airbnb profile and pay $ 80 a night for the veranda of our apartment in St Kilda with fresh linens and breakfast guaranteed, or they can contact me via couchsurfing and crash for free.

It made me think about how my personal priorities had changed since I was a young couchsurfer traveling through Europe, the United States and Australia a decade ago. Back then, there was a fine art of reading dozens of couchsurfing profiles for the next town or city on the route and writing personal and authentic letters to the most attractive of them asking to stay home.

Today when I travel I prefer to use Airbnb – partly because I can usually afford to rent an entire apartment precisely in the area I want to stay – but also because more often than not I will be looking for a place to write. , so I must invest in a quiet and comfortable workspace.

But when it comes to accommodation, I’ve found that I much prefer to host couchsurfers than Airbnb guests.

There is something more genuinely nomadic about couchsurfers – they come to terms with human goodness in a way most of us stop doing as adults. Plus, couchsurfers invariably have more interesting stories to share about hitchhiking across the country to be here, and they usually have lower expectations.

Simply put, the exchange becomes more human when money is taken out of the equation. The experience transcends the grind and can take me back to the days when I too was a free lonely traveler surviving the kindness of strangers.

Any human interaction with strangers comes with risks, as recent reports of an Italian couchsurfer drugging and raping hosts prove. The key tip is to be careful of the referrals your guests have accumulated – and only take guests whose identities have been verified. In your first online chats with guests or hosts, insist on a level of honesty and simplicity before closing the deal.

For those of us who spent nascent years traveling the planet when couchsurfing was in its prime, revisiting your own couchsurfing profile can be a confrontational experience. Can many of us honestly claim to be true to the idealism that initially drew us to this rather utopian, unmonetized travel portal?

Here is an excerpt from mine: “My mission is to participate in social change, to love my friends, to work for the planet, and to expand as a writer … I like to explore, to broaden my horizons, look for the light by dipping your toes. in the dark, writing to the world and constantly expanding my networks of close friends all over the world.

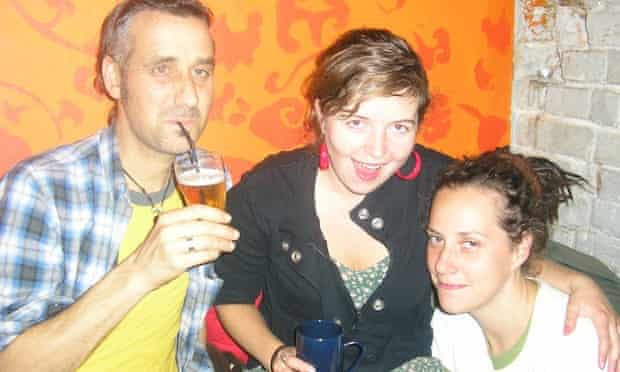

Over more than 10 years and in 10 countries, I have recorded 34 positive references from people I have stayed with and not a single negative one. People like Paul, the New York nudist and poly-pride activist who opened up his entire loft on Kekalb Avenue to anyone who asked to stay with him, meaning his apartment housed up to 20 travelers from all over the world. by night. Or Cashia, the Polish Greenpeace activist with whom I stayed in Warsaw and helped prepare food for the homeless through a Food Not Bombs stand she ran in the market square. Or Dot and Roger, the progressive Christians who welcomed me and my boyfriend to stay with them in Portland, West Victoria on a trip home from Adelaide. They left out the fresh eggs from the hens in their garden so that we could make our own breakfast.

Couchsurfing tends to attract like-minded people whose values match the idealism of the concept – but with pay-per-night hosting sites, the deal can become a lot more mercenary.

We would like to think that becoming a homeowner does not change us, but in reality it probably is. Since buying an apartment in St Kilda about two years ago, I have kept my couchsurfing profile, but have also decided with my partner to open our back room to Airbnb, Windu and Gay hosts. to help cover mortgage loan payments.

A number of guests stayed with us, but the exchanges were nothing like the jovial affinity I had grown to enjoy with other couchsurfers. Instead, we had young couples from Adelaide who just wanted to come to St Kilda for a party weekend and seemed to prefer to keep their communication with us to a minimum.

And we had an elderly Dutch couple who took a look at the size of the room and politely announced that they were going to find a hotel down the road instead.

Sure, some of the paying guests were great, but what is noticeable is the heightened sense of entitlement that the money transaction permeates. When accommodating these guests, the apartment ceased to feel like our own home and took on the dimensions of a serviced apartment where family freedoms had to be lost.

There is no doubt that these sites work wonders for people in different circumstances. Their practicality is determined by many factors, including the physical layout of your home (whether you can offer a separate or semi-detached living space) and your financial needs. I’ll keep these profiles active for the times we go and want to rent the whole apartment (that’s a great aspect of these sites).

But we made the decision to no longer take paying guests while we are in the apartment and to just host couchsurfers. I prefer the nature of the exchange which makes me feel like part of a global community of people seeking meaningful travel experiences outside of the mainstream capitalist economy.

For me, couchsurfing has always been about idealism. And like most ideals, it only works and becomes real when we do.

Comments are closed.